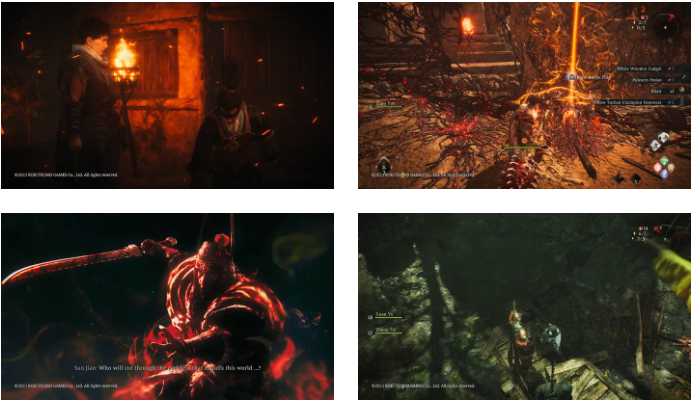

When you feel like you’ve reached a dead end in a game, whether it’s early on in Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty or at the conclusion of what is supposed to be the introductory task, it’s usually reason to be concerned. During the Yellow Turban Rebellion, you are thrust into the center of China’s chaotic Three Kingdoms era and face one of its powerful commanders, whose strength has been increased by a cursed elixir. Surely, as in Sekiro, this is intended to be a trick boss that you have to lose against? Or perhaps there’s a simple exploit hiding right in front of you, like the Taurus Demon in Dark Souls? Thankfully, after almost an hour of effort, I realized it was the latter—the cost of using the actual Chinese audio while neglecting to read the subtitles while the fight was intense.

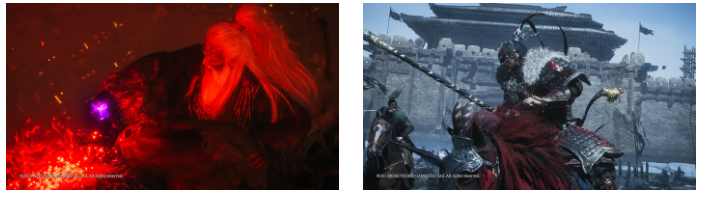

Putting yourself through this harsh initial obstacle may be indicative of Team Ninja’s “masocore” mentality, but it almost seems like a departure from the remainder of the marathon that lies ahead of you. The company has abandoned the Sengoku-era Japan-based Nioh series in favor of new features and gameplay that make Wo Long one of the most approachable Soulslikes I’ve played in a long time—all without just putting it on easy mode.

Having spent two decades hacking and slicing through this historical period in the Dynasty Warriors game, Koei Tecmo is no stranger to the Three Kingdoms era. The translation of “musou” to “Soulslike” has a dark fantasy element because everyone exposed to this enigmatic substance is being transformed into demonic monsters, even the warlords vying for control of its power. It seems appropriate that these characters battle with you, considering the many larger-than-life heroes who have practically become myths, not only in the musou games but in countless other Chinese adaptations as well. If you’ve played Nioh 2, you may recall that on a few missions, you were periodically joined by an AI-controlled buddy. This is almost the standard in Wo Long, where you start a task with one ally and it ends with a boss fight at the end. You may also call out other allies from your growing roster.

That is not to mean that renowned figures like Liu Bei, Zhao Yun, or Cao Cao would fight your battles for you; nonetheless, encouraging them will make them far more aggressive. Though it’s the more enhanced and more fluid fighting system that makes me want to take on its challenges alone, I treat them almost as a security blanket so I know someone has my back and can charge in more recklessly.

This is partially due to Nioh’s more lenient adjustments. For example, falling from a cliff or into the sea does not instantly result in death, nor do sprinting or even standard assaults deplete stamina. Even when you die, you don’t lose all of your Qi—Wo Long’s version of souls for character leveling—but you will need to get even with the person who murdered you if you’ve lost some. A dedicated jump button has also made movement much easier. It has a double-jump that makes it much easier to flip up to higher ground, which in turn provides you more possibilities to leap down for an unexpected takedown. Keeping your distance from your adversary allows you to sneak up on them and pull a backstab. Although it would have been nice to have had a crouch button, it helps that your enemies are frequently quite nearsighted.

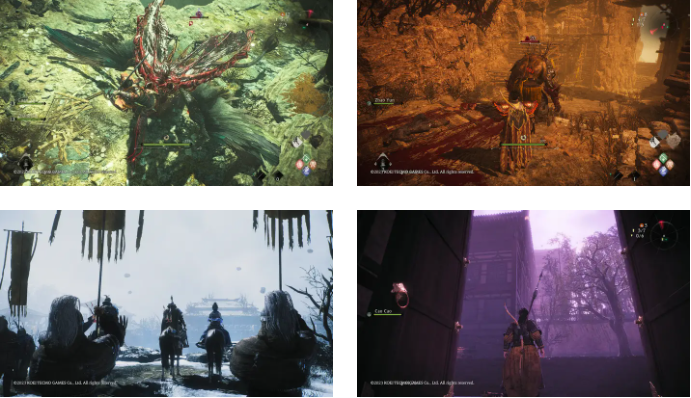

But enough about that; let’s return to the fighting and specifically the stamina system, or as Wo Long would say, your spirit gauge. An orange-red bar that advances to the left for the former and a blue bar that goes to the right for the latter represents the progression of Nioh’s Ki meter, which now has a gauge that can flow both positively and negatively. As you’ll be utilizing spirit a lot for your harder strikes, wizardry spells, and weapon’s martial arts, it makes sense that you’re seldom in the blue. However, normal strikes don’t utilize spirit, therefore the only things that will keep your spirit out of the red are these and deflecting assaults.

This is where things become interesting—deflecting. Experienced players of Soulslike would know that blocking is not as effective as evading, and that Bloodborne (which has the same producer as Wo Long, Masaaki Yamagiwa) does not use shields at all. Since the deflect button in Wo Long is also the button for escaping, it may appear counterintuitive at first, but in practical application, it’s rather clever. My natural reaction is to parry an approaching assault, but if I time it well, the parry turns into a deflection. It seems like I can still try to dodge but occasionally also luckily deflect, and before long I was basically preparing myself to ‘dodge into’ an attack in order to deflect it. Instead of having a separate parry button that you’re hoping you’ve timed well enough to escape a terrible punishment. It soon becomes crucial, not only because it throws your opponent off-balance and opens the door for you to react, but also because it aids in regaining that crucial spirit. It’s also less demanding than Sekiro’s extremely exact and difficult parries since Wo Long allows you to parry anything, and I mean anything. Sekiro was mostly a fighting game where you had to know when to jump over a sweep or evade a grab.

This is particularly true in situations where your opponent is about to deliver an unblockable critical blow—which is clearly indicated by a wind-up animation and a demonic red aura—and you are faced with the choice of either losing badly or turning the tables and severely weakening your opponent’s will to the point where they are vulnerable to a deadly blow. In fact, I found myself eagerly awaiting and even trying to set up these attacks—not to mention that it looks so good to parry big hits. It is really satisfying to have the camera crash-zoom in cinematically when I follow through with a lethal strike; the crackling soundtrack that goes with it creates the same sensation as when you bowl a strike.

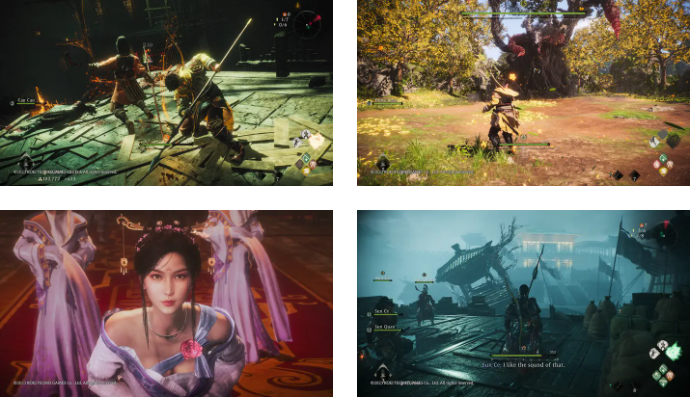

Because of its connection to Wo Long’s morale system, landing deadly attacks is another way to make the game simpler. In Wo Long, morale is represented by a number over an enemy’s head. It functions similarly to an enemy’s level in a role-playing game, allowing you to determine whether to take a chance or to avoid them. The distinction is that these values are mutable, meaning that, similar to shifting weights from one side of balance scales to the other, striking an opponent fatally decreases their morale while you gain it. If you continue on your current winning path, you will eventually become a heavyweight fighter capable of facing any evil opponent that may be hiding around the corner. It’s important to remember that dying also results in the loss of any morale boost, so there’s a true risk/reward tension.

If you think the punishment is too harsh, don’t worry—flags serve as both checkpoints and, in line with the Three Kingdoms motif, a symbol of your dominance over the battlefield. Your fortitude rank increases as you plant more flags; it also has a number that is the lowest point at which your morale may drop. Stomped by a boss who has a twenty-percent morale? So that your default morale is the same as theirs, place all the flags in that level. In a variation on how you engage with other players who have fallen, skilled players who survive can even enhance their morale beyond this point. You can contribute one of your healing potions in return for increased morale. It’s similar to having a dynamic difficulty setting that pushes you to fully explore every level.

Though graphically things do eventually change beyond the usual devastated villages and hollow mountains, it still offers additional reason to interact with the settings, which, like Nioh before, seldom inspires the imagination beyond the conventional closed doors, blocked roads, and returning shortcuts. It’s also odd that Team Ninja hasn’t thought to redesign a loot system that is so abundant in quantity—a holdover from Nioh’s original design, which gave its gear limited durability—that the only sensible and effective solution is to equip the item with the highest number and sell the rest. It makes sense that until very late in the game, I was hesitant to visit the smithy to improve anything, knowing that you’ll probably discover even better gear in the next task regardless.

While a new setting might imply a new chapter, I would almost rather refer to Wo Long as a Nioh-like, or more accurately, as the follow-up that Nioh 2 ought to have been, improving its customization and systems, eliminating most of the bloat, and adding an intriguing evolution to its foundations that makes its challenging core more manageable on its own terms. It is undoubtedly more pleasant to travel with comrades, but you can feel completely satisfied if you can halt a warrior twice your size who is possessed by a demon, respond with a spear that plunges from the sky, and reduce his morale to nothing in the process.