The Atomic Heart review showcases the industry’s growing concerns through its depiction of confusion and fear

A game that is just marginally engaging is submerged in a problem of its own creation, which is indicative of an industry dilemma that will only get worse.

While many concerns have been raised concerning Atomic Heart, maybe the most important one is still just what it is. It turns out that Atomic Heart doesn’t really know what it is either, much like a lot of games that bash around, start debates, and define themselves by comparison to other, adored games rather than on their own terms. If you’re anything like me, you’ll probably figure out how to beat the game before you even have an idea.

You will probably already be aware that it is, at the very least, “controversial” before you reach that stage, and there haven’t been many disputes. Developer Mundfish has faced criticism, as we’ve covered in more detail elsewhere, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the company staged some ill-timed marketing events in Russia during which large red banners with the words “Glory to Soviet Engineers” were displayed. These events coincided with the nation’s own, horrifying, and land-grabbing invasion of Ukraine.

Regarding Mundfish’s finance, there have been questions and misunderstandings because one of its major backers has ties to state-run Gazprom in two different ways. And, of less significance, queries regarding the location and history of the studio itself. A depressingly vague answer on the war in Ukraine was given, something along the lines of “global team… innovative game… pro-peace organization… against violence against people,” etc. For good measure, here’s another vintage gem: “We do not comment on politics or religion.” Then there’s the data problem, which has Mundfish vehemently claiming that the notice on its Russian shop website is “outdated” and warns customers that their data may be seized and given to Russian state agencies. The issue around “racist cartoons” is another. (Interestingly, they were there in the PC version, but since the Xbox version’s release, many TV screens where we played have been completely blank white.)

There’s still more! The game’s scene-stealing ballerina robots, which you also find out are sex robots, have drawn comparisons from Ukrainians to Yulia Tymoshenko, a prominent Ukrainian politician who is reportedly despised in Russian political circles for her unusual blonde, plaited hairstyle and her steadfast support of the EU, NATO, and the anti-Eurasian Customs Union positions. Finally, but just as importantly, Atomic Heart will be released on the anniversary of a statement made by Vladimir Putin that effectively started the conflict a year ago. Because of all of this, Ukrainian authorities have apparently contacted Sony, Microsoft, and Valve to request that the game not be sold in the nation, and merchants there have reportedly refused to stock the game. Regarding all of the aforementioned, Mundfish has not reacted to any of Eurogamer’s requests for comment; nevertheless, our story goes into further depth about a lot of things.

Of course, it’s easy to write off a few dubious errors as clumsiness—many other games in our extremely uncomfortable, foot-in-mouth-loving business have made and then corrected a dubious error. But after three or four, you’re really getting close to the point of ignorance and innocence. Fool me twice, that kind of thing. By my calculation, Atomic Heart had already seen at least seven before it was even out for the entire day.

Atomic Heart: What Is It? When you consider all of the aforementioned issues collectively, Atomic Heart appears to be a classic example of dog-whistling: every controversy has enough plausible deniability to never quite be resolved; concerns about anti-war statements are taken seriously; there is a problematic state investor in Russia; the racial content of that cartoon was overlooked; the “Glory to Soviet Engineers!” rhetoric was out of date; and many people have that one specific, historically significant Ukrainian hairstyle! Additionally, modifying the release date would, uh, involve some paperwork? Nevertheless, there is enough inferential evidence to conclude that something is, at the very least, strange about this.

The odd thing is that this all stands in sharp contrast to the game itself. Atomic Heart is not so much a resounding support of Soviet Russia as it is a sharp condemnation of it. The narrative denounces the power conflicts, corruption, and deliberate ignorance of bureaucrats within the Soviet Union. That’s not to say that it’s a very good one, and as allegories in AAA games frequently are, it’s conveyed with all the subtlety of an exploding pig (hardly HBO’s Chernobyl), but it’s there none the less. The issue is that it has caused some confusion with its own bravado, clamor, puffed-up chest, and macho-baiting marketing; moreover, it is still unclear what the true aims are behind all of that noise.

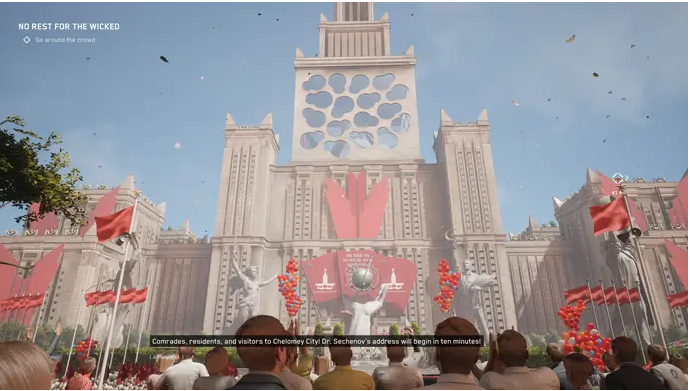

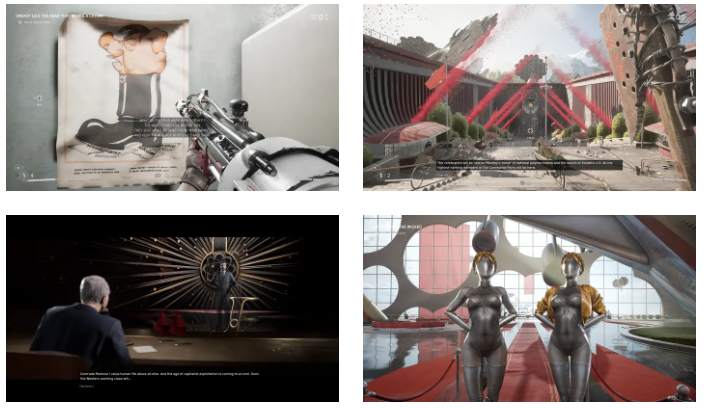

The best example of this is found in its opening sequence, which is a solid thirty minutes of combat-free, linear storytelling in which you explore the streets and canals of a magnificent, floating metropolis in the Soviet future (Bioshock Infinite: check). It’s jam-packed with extravaganza, with confetti raining and you being flown away on flying tours under azure skies. You’ll hear radio fanfares blasting as you make your way past brutalist landmarks, enormous, immaculate sculptures clutching enormous, golden sickles, and maglev bridges. We bring you to the robo-sex-ballerinas, who breast-boobily stare at you from across the room, moving as if they were driven by an OpenAI chatbot that only feeds on men-writing-women jokes. The main character, a spec-ops guy with an undercut named P-3, sneers at every polite ‘bot he encounters and treats them like a cheap, annoying BJ Blazkowicz. He also makes fun of Charles, his helping magic AI glove, and all of the game’s challenges, locked doors, and puzzles.

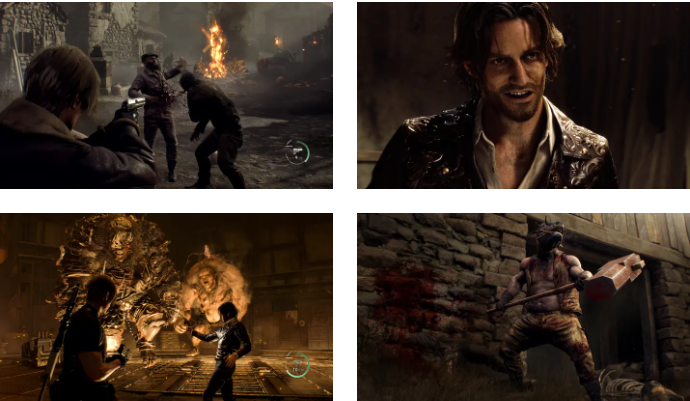

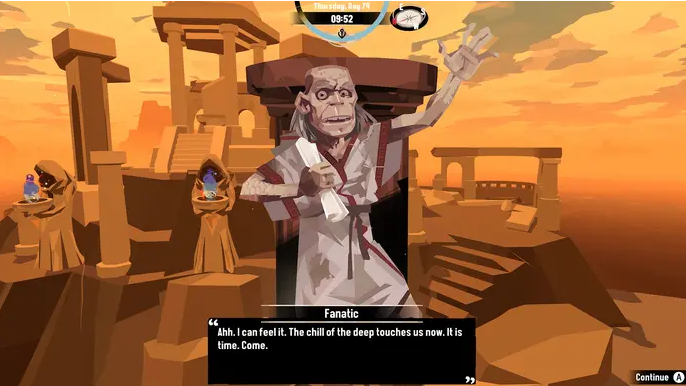

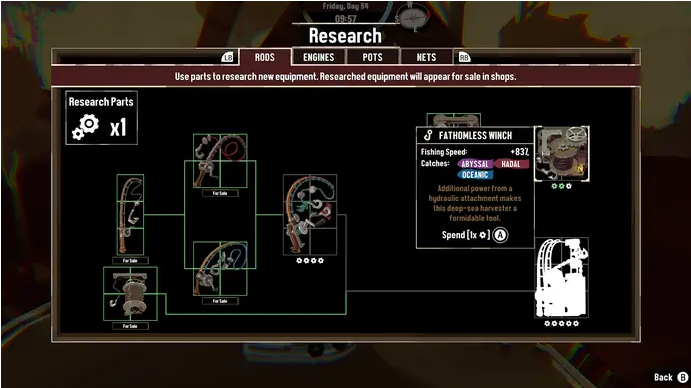

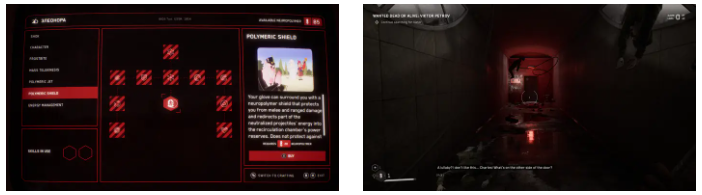

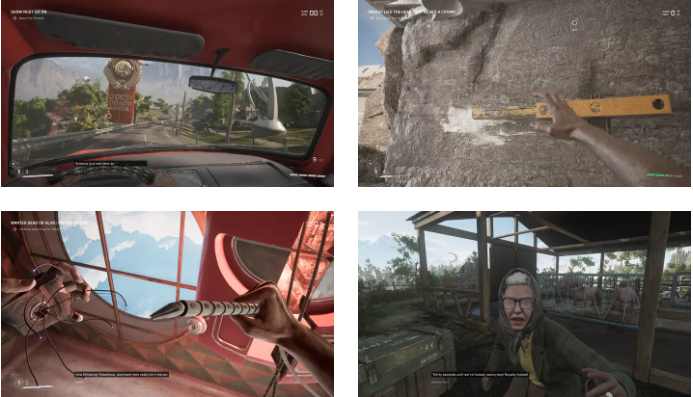

Following that protracted pseudo-cutscene, however, the action abruptly shifts to a horror game akin to Resident Evil, as you venture into a haunted house of a testing facility and scrounge around in the shadows between blood streaks and mutilated corpses for makeshift weapons and spare ammunition. You also have to look for lock combinations and creep past animatronic moustaches that appear frightfully overpowered or, more frequently, set off the alarm and frantically clonk them on their armoured heads with a taped-together axe. After that, you’re on the surface of Metal Gear, an open world game with tons of cardboard boxes, patrolling buzzsaws, and security cameras every five yards. Before you know it, you’re back down, crafting shotgun ammunition and upgrading your backpack storage, chilling in Fallout shelters watching charming 50s info-toons with the Soviet counterfeit Vault Boy, and scaling yellow-painted ledges like, well, anything developed by Sony.

That being said, a lot of Atomic Heart’s issues are far less dramatic than the debate would have you assume. When taken as a whole, it’s derivative and too ambitious, a game created based on the elevator pitch of a fourteen-year-old: it’s a grab-bag of concepts from previous games that they made their own. a free world! demanding warfare eerie gore Hot robotics! Arms! Ascending! Enigmas! Sneaky! Creating! A grandmother, but with firearms and profanity! Enchantment! Everything fit together like a playable Homer Simpson car. Instead of being driven internally by a well-thought-out design, the game appears to have been dragged through production by its marketing staff (picture the trailers, think of the back-of-box bullet points!). Which is unfortunate because these different components are frequently really wonderful on their own.

The marvelously detailed little skits about chasing off wicked capitalist pigs in the not-Vault-Boy animations, for example, are set against the sumptuously creepy backdrop of this game’s menus, which flicker and fuzz in emergency red over the wails of distant air sirens. To be honest, combat is a tad simplistic. It can occasionally seem like the infamously difficult first-person fighting in The Elder Scrolls, but without the blocking and only some of the spells – chopping harshly with one hand and zapping with the other. Furthermore, adversaries frequently move quicker than your camera can detect them on the console, without making the response unplayable. You’ll also frequently be punched to the ground from behind without even realizing the adversary was there. The monster also engages in drag combat, which frequently consists of constantly dodging and scraping with little blades and potato-gun shots to deal minuscule damage. Yet! As you become familiar with its peculiar rhythms and discover a little more left-handed synergy, it does eventually come together.

The best part—and this is the most unexpected—is that P-3 has a solid plot and eventually grows to be—gasp—quite lovable. In reality, those early hours are a well-planned deception, as he transitions from being a fervent believer to someone who has been deceived with fury. The foundation of the game is present and can be pretty strong at times, but like many big-budget action games with aspirations of Saying Something, a lot of momentum is wasted to plottiness as a tight six-hour tale is stretched out over more like fifteen to make way for all the open-worlding. By his own admission, P-3 is not a brilliant man, but Charles, his friend, is an extremely intelligent man. He becomes weirdly sympathetic as the former progressively has his universe broken by the latter’s polite, if occasionally condescending, explication. A militarized fanatic is realizing he was merely a tool on the wrong side and that his belief that he was fighting for a worthy cause was justified (look around at all this shiny, progressive utopia on the surface).

The truth is that video games are becoming more and more tainted; in Atomic Heart, the ambiguity practically seems to be the purpose.

In between the incisive work in the eerie, NERVesque Politburo and the haunting hospitals, there’s some clever work to back it all up. The soundtrack, by composer Mick Gordon—who told us why he chose to donate his money to Red Cross Australia’s Ukraine Crisis Appeal—is astounding, ranging from enormous, sweeping orchestras to techno-djent. The cutscenes are overly lengthy, but the score is worth it. This is a rare instance of a game realizing it’s not constrained by the standard principles of physics that restrict movement here in the real world. The camerawork is smart and, for once, a touch mischievous, drifting the point of view across rooms like a voyeuristic drone.

Underneath its own loudness and between the creaky joints holding it together, there’s some nice material here, fundamentally. In a way, Atomic Heart represents the odd place that video games generally find themselves in. Its marketing and public image have, if anything, given the impression of being designed to appeal to the reactionary audience—those who know the answer to more than seven decades’ worth of controversy, who would stand by it even if they disagreed, and who profit from resentment and hatred. With a kind of siege mentality—they’re out to take our games with all their politics!—its taunting, unapologetic attitude unites supporters against critics. This is reminiscent of how some segments of the Russian public have, if anything, only strengthened their support for the war in the face of needless Russian deaths. For them, criticizing a game equates to criticizing everyone who has ever considered playing it. Ignore the irony of the fundamental theme of the game.

It also brings to mind the mess that video games are getting into more and more and how hard it has been for the industry to adapt to it. The truth is that the video game industry’s insatiable need for cash is compromising games more and more. This may be seen in the bargains artists have to make to launch their passion projects in a commodified market or in the top executives’ constant need for more money. More games are being linked to governments, kingdoms, autocracies, contributions, and, in many cases, very horrible individuals on a daily basis. Specifically with Atomic Heart, the confusion almost seems to be the point, morality weaponized against the wielder through whataboutism and panic – and all of it here at the very heart of the engagement economy, leading to eyeballs, and eyeballs leading to sales. This confusion is similar to the discord sowed by Russian bots popping up in Facebook groups on the left and the right.

That’s one cynical reading, anyhow; the problem with Atomic Heart is that it’s hard to tell for sure. There will be more issues with other games. But since every controversy and event is unique, we must approach them individually. No two debates are exactly same, and neither are situations. Despite this, I believe the message remains the same: just because someone uses your desire to do the right thing against you, doesn’t mean you should give up trying. You should thus put forth more effort.