Let’s start off by saying that discussing how much fun the parts of a video game where you get to play as Erwin Rommel are can be a little odd, or worse. But this is the peculiar predicament that Company of Heroes 3 places you in. A rather unbelievable game that puts you in the shoes of a Wehrmacht commander and was released the day before the anniversary of the conflict in Ukraine is a war simulation game that manages to be successful in spite of its dubious release date and questionable design. The fact that Company of Heroes 3 has gambled so carefully with its setting and tone contributes significantly to its outstanding quality.

That being said, this is hardly shocking. For a while now, Relic has been the epitome of the RTS (real-time strategy) genre. After Dawn of War 3, which bet much more heavily on providing troops active powers and more clearly defined “lanes” on its multiplayer maps, some people might have been concerned, but they shouldn’t have. A safe-bet sequel, Company of Heroes 3 is a response to the studio’s obvious excitement at the creative possibilities of the first film. It’s a conservative’s dream come true. All of the things you enjoyed about Company of Heroes in the past are back, plus more, and everything is slightly improved. There aren’t many, if any, significant innovations—just tweaking, iteration, and dial tinkering.

However, they are nearly universally successful, with the dials set precisely where you would want them to be: for large explosions, tactical demands, and magnificently recreated sounds; in other words, they are dialed right up to the point just before the last notch on the Realism Scale where you hit the range known as Excess. As a result, real novelty or proper creativity are replaced with an extremely high level of competency. Most of the time.

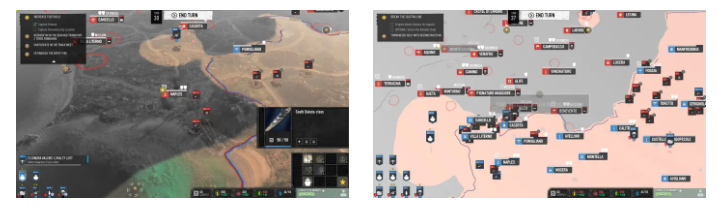

I have a problem with CoH 3’s Italian Campaign. With CoH 3, there are two single-player elements, which is more than ever (a recurring motif) and maybe more than you’ll ever need. The Italian version is large, even by series standards, a sweeping spectacle that combines the simpler, arcady pleasures of classic Relic games, such as the planetary conquest of Dawn of War: Dark Crusade, with the wonderfully bureaucratic components of the sandbox overworlds you’d find in the Total War games.

On paper, a lot of stuff is excellent. Starting from the point of Italy’s boot, you ascend the country by subduing towns of all sizes, besieging cities for many routes, risking ambush on speedier roadways, or choosing slower routes across the sun-dried hills of the Mediterranean. Meta versions of the troops, weapons, and fuel from CoH’s real fights are the resources to be managed. There are also a range of tactics to use, such as naval bombardment, artillery, and parachutes. You can see Creative Assembly’s combined talent at work; one would assume that the two Sega-published strategy masters are seriously hiring each other. As someone who has long yearned for the return of stomping through maps and dousing them all in your colors, as we did during the Dawn of War era, I was extremely excited for this to succeed.

Its blend of pulpy enjoyment and rigorous strategy, with a sort of no man’s land at the conclusion, is where the troubles lie. Many aspects of the game feel overly simplistic: auto-resolve is only partially implemented in certain engagements, which results in a lot of manual fighting of brief, repetitive skirmishes on the same maps (somewhat abstracted locations try to break things up, but not enough). The fact that they are reused makes sense: Unlike the more generic chunks of land you may encounter in Total War, Company of Heroes maps are by necessity more complex, with strategically placed structures and cover systems. However, in this case, they age quickly. Similar to that, there are a ton of systems here, but you really don’t need to interact with them at all for the most of the campaign—certainly not for the first third. You just need to slowly advance your little men up the spine of the country, healing themselves for virtually nothing every turn (companies’ overworld health also didn’t seem to affect their actual strength in battle, as far as I could tell), until they reach a choke point that may be strong enough for you to use your battleships to launch a few artillery strikes on it before moving on.

The’sandbox’ aspect of things is further limited by the wish, and maybe necessity once more, to present a particular tale of the liberation of Italy and its resistance fighters by US and British forces. In terms of sandboxes, this one is long and narrow, requiring you to begin at one end and end at the other while starting on the same team every time. Whichever option you select, your advance will be dotted with sub-objectives from three factions of allies: an Italian resistance commander, two quarreling US and British generals, and others. These do provide some variation and dynamic. You’re compelled to give in to their demands and make an effort to satisfy all three of them. Usually, this involves making fairly straightforward trade-offs between upsetting and pleasing each other, tied to a loyalty system that advances you through a tree of bonuses based on how satisfied or unsatisfied they are with your choices. However, when you’re trying to, you know, win a war, sometimes this can devolve into a kind of constant badgering. Visit an athletic meet! Preserve the ancient church! As in, extinguish a fire! Go on now! Give me a break!

Having said that, Company of Heroes still has this as a recent addition. Despite the annoyances, engaging in multi-stage, goal-filled missions inspired by actual conflicts is still incredibly fulfilling. The Italian landscapes are a welcome diversion from the usual fare and may appear like a “where’s left in WW2?” choice, but they are exquisitely rendered. Fundamentally, there is still undeniable satisfaction in moving little men over a large map. This place is enjoyable, especially after the easier open hours expire and the resistance gets more varied and fierce. But don’t anticipate the massive replay value or the more endearing schlock of previous games whose main draw was conquest-style adventures.

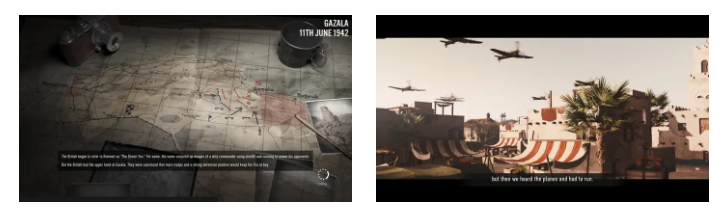

Remember that this is only a portion of Company of Heroes 3. North African Operation, an eight-mission linear plot that mostly replicates the single-player portions of previous Company of Heroes games, makes up the other half of the single-player experience. This is the one that puts you in the role of Rommel, the well-known “Desert Fox” of the Second World War. Rommel has been romanticized and mythologized in the year following World War II, being shown as a sort of “gentleman general” who is aloof from all that awful Nazi things. However, even in the context of detached, ironic moustache-twizzling and the undeniable fact that humans find a strange kind of fun in playing the virtual villain, role-playing as a man who was known to support, or in some historians’ words “worship” Adolf Hitler for much of the war remains, at best, deeply strange. A “gentlemanly” Nazi is still a Nazi. Rommel, for example, eventually died as a result of a plot to overthrow Adolf Hitler.

Even if the team established this very impossible goal for itself, Relic has at least been wise to assign it. In order to refute the notion that the North African conflict occurred in some sort of civilized vacuum removed from the unpleasantries of the war, the narrative of this portion of the conflict is told from the viewpoint of local civilians in between missions, illustrating the death and destruction among their homes. You will hear the shouts of the British troops as much as your own as you advance. You read letters home from a local man they’ve recruited while the screens load. Rommel and his DAK (Deutsches Afrika Korps) are not idealized, nor is there an overabundance of sanitization or correction. It is given exactly as it was, or rather, as it is, in the context of its whole historical occurrence, as all history ought to be.

Though you can’t help but think that the more vile areas of military history games would still happily hop into their Panzers while ignoring that backdrop. Relic has made an effort to lessen their justification for doing so. However, there is a persistent feeling that a sequence of missions from a certain character’s perspective would always fall back on a type of pity without extra care, regardless of how many heartfeltly rendered cutscenes you put around the borders. Generally speaking, I would argue that it is very acceptable to offer your own critique as a viewer, but this is the weird, hazy space where engaging in active gaming diverges from the passive experience of other media.

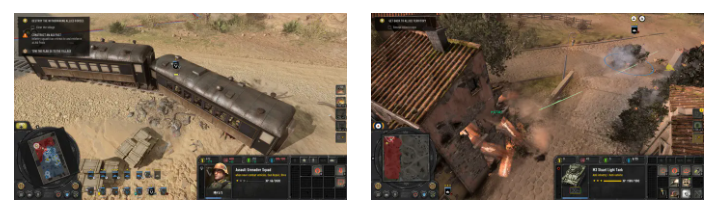

The missions themselves are excellent examples; they are dynamic, multi-staged, demanding, and varied. Leading a small force of tanks will give way to retrieving and reusing wrecked vehicles, surviving assaults, pincer movements, and counterattacks. The only probable critique is that such sharp countermeasures and cerebral outflankings have little impact if there isn’t a larger backdrop outside the staged missions; otherwise, you just have to follow orders to complete the goals. It almost makes you want for a hybrid of the two campaigns, in which you navigate an overworld map and may virtually play through the maneuvers before carrying them out. However, it’s actually a minor quibble because the missions are fantastic.

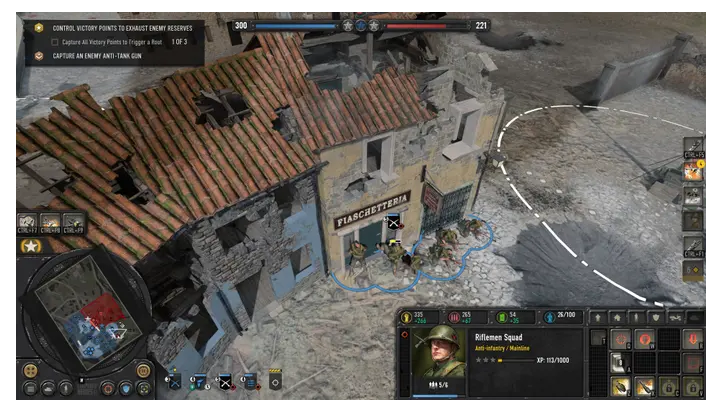

In relation to that, Company of Heroes 3 has included a fantastic feeling of spectacle that flawlessly matches its little adjustments. With sand dunes, desert ruins, bell towers, and captured castles, maps now have a lot more “verticality”—that darling word beloved by developers—because the height of your troops now directly affects sightlines, sight ranges, and cover. Everything is capable of being destroyed by explosion, which fits in pretty well with a campaign centered around blasting objects with tanks. The series’ renowned accuracy in sound design is also a joy, sounding both realistic and flamboyant at the same time—a classic Hollywood meets historical moment that resonates loudly in your ears.

In actuality, CoH 3 is elevated by the same elements that made Company of Heroes the legendary wonderful game that it is. With the exception of the occasional rogue tank, Relic’s long-standing mastery of battlefield context is better than ever. Squads naturally line up outside buildings or hop low walls to neutralize enemy squads (breaching is a new mechanic that is, to be honest, almost gimmicky, as it is essentially the same as just lobbing a grenade into a building as you did before). Compared to other RTS games, it has greater tactical complexity, but it also has more intuitive gameplay as its strategies make sense: avoid running troops over wide highways or, as of late, up blind slopes, and instead target tanks from the side or back. There’s a sort of pre-made logic to every successive layer of complexity that is added, such as more scouting units, light and heavy tanks, structures, and tools for constructing and combating traps.

That being said, be ready for a challenge as usual in multiplayer, where my brief and disastrous attempts at taking on other players online have shown me that CoH 3 has a low entrance barrier but a very, very high skill ceiling. The positive is that there is once again more diversity than before: 14 maps, four factions with three sub-faction “battlegroups” apiece, the most of any series at launch, co-op, and even modability ready to play right away. There is a good deal of tonal similarity, but there is also a wonderful historic texture. I love how special forces from other parts of the world, like the Gurkhas, Australians, and Canadians, or even just different British accents, like cor-blimey-guv and still effing-and-jeffing Welsh, are used to remind us of the Second World War’s global scope, human cost, and intimate moments in between the action.

Again, the end product is a game that is more safer than it is creative, one that mostly builds on the qualities already present—human touches, bombast, an unmatched blend of tactical intricacy and contextual immersion—rather than introducing anything new. Company of Heroes 3 is just Company of Heroes, just better and more abundant. That’s more than sufficient in this instance.