The combination of fishing and Gothic horror with Lovecraftian themes is a great hook, but Dredge’s basic loot-and-upgrade rhythms are too obvious to draw you in.

Among the creatures you’ll pull from the darkest recesses of a desperate fishing simulation when the game’s encyclopedia describes, Dredge is the miserable marine sausage that begins to collapse when it gets dragged up into a torturously low-pressure environment. It serves as a brief reminder that there is always a shift while going from the depths to the surface. Gorgeous aquatic animals turn into monstrous abominations when they are crushed and distorted by the harsh operational conditions of a world they weren’t meant to exist in.

In Dredge’s instance, they become right angles, with each vibrant 2D fish depicting the center of a group of bricks that need to be inserted into a cargo hold that is shown as an expanded grid. It’s a bloodless shortcut to actual commercial fish processing, when fish are sliced on the deck into marketable morsels before they’ve had a chance to suffocate. Smaller creatures, such as the snailfish (which, despite the description, doesn’t implode here), occupy a few squares and may be readily inserted into openings between the hull and your ship’s engine or lights. Larger hauls, such as sharks, create strange, rectilinear Christmas trees of fins and teeth; packing more than one in is never easy, but maybe if you rearrange your mackerels a little, space will appear on its own.

The predators that prowl the game’s 19th-century archipelago by night and Dredge’s fishing excursions’ difficulty curve are both influenced by this subtle spatial puzzle. Every journey resembles purposefully filling up the Tetris board, risking a game-over to clear several lines at once when you let your catch go at the market. At the core of a ten-hour game of fishquests and upgrades lies the One Clever Mechanic, which is unsettling in many aspects but seldom as aggressively, rewardingly horrible as it would initially appear.

The game Dredge starts with your character, a salty relative of the granite-faced Ancestor of Darkest Dungeon, flying aimlessly through the fog. You wake up on the dock of Greater Marrow, a tidy little woodpile of marketplaces and shipyards beneath a candy-striped lighthouse, after the inevitable disaster. Right away, the mayor gives you a new bathtub and makes you an official town fisherman. What became to the former fisherman? From where is this strange mist coming? And why are you getting the stink eye from the lighthouse keeper? Well, that should all be forgotten—at least for a few hours. Simply throw a line!

Fishing sites line the surrounding ocean, visible in all weather conditions as you plod around in your initially underpowered sailboat. The places are identified by bubbles with gray shadows idling underneath. Dredge’s system is a collection of reflex-driven minigames that are in line with virtual fishing in general. For instance, you can haul in a catch quicker by pressing a button when a revolving cursor reaches a green zone. Numerous fish species you may see are well-known: squid darting in temperate shallows, red snapper in the southern tropics, and massive eels behind the crags in the north. Occasionally, though, you may unearth something that seems familiar, such as an octopus with heads on its tentacles.

A few of these eerie mutations are based on more terrifying real-world creatures, such as the notorious Anglerfish, which has a lure that glows in the dark. Others are flailing Jungian metaphors for the violence and greed of the surface-dwellers: a flounder that is all eye, a shark with a jaw as long as its own body. Every major island’s fish market offers them for more money than the species from which they are derived. Whatever your thoughts on abyssal perversions, it seems they make delicious food.

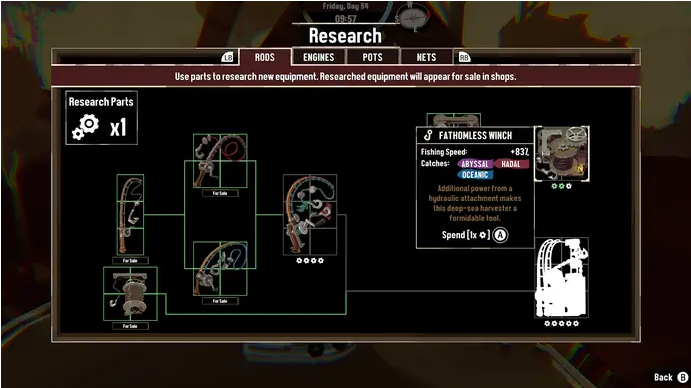

You spend the income from each haul on repairs and improvements – in particular, greater cargo capacity and specialist fishing equipment that allows you harvest diverse ocean locations, from hot volcanic seas to the deepest ‘hadal’ zones. Along with salvaged wreckage, you’ll find strange bottled messages, melancholic lost riches to flog to the world’s lone dealer in non-piscine commodities, and planks, clockwork components, and bolts of cloth—all necessary for the bigger enhancements.

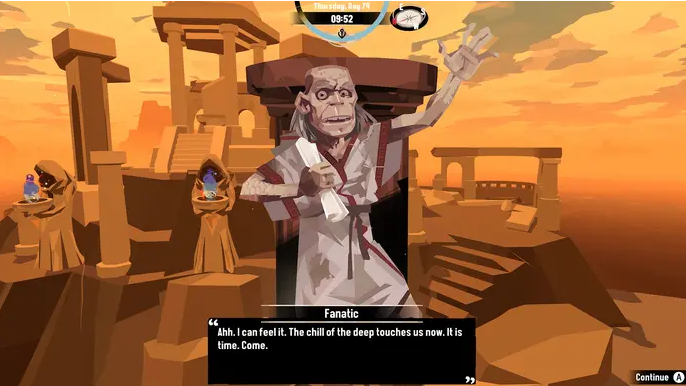

In addition to your developing fishing powers, you embark on basic, two-step story missions that carry you across and between islands, often seeking for a rare type of fish, with the odd puzzle twist such as obtaining explosives to clear a passage. There is just one main questline, which involves a solitary Collector who has a list of eldritch artifacts to unearth from every area—possibly for completely benign reasons. He provides cursed but useful supernatural abilities in exchange, such the ability to teleport to the center of the globe map or to use a phrase to exhaust a fishing area. Typically, netting these mysterious items entails resolving a nearby, incidental issue, such as assisting a stranded pilot in leaving a mangrove swamp that continuously rearranges its structure or supporting a researcher investigating the enormous, irritable cephalopod at the center of a tropical reef.

Simple to the point of drowsiness, it’s an encompassing framework with bite-sized story pieces and market-proven progression methods. Dredge leans more toward the chillax loot ’em-up genre than the nautical survival horror, even if it aims to be both. Sunless Sea is undoubtedly influenced, however this game allows you to look away across gorgeously buckling waves that beg to be broken through, whereas Failbetter’s game fixes your perspective on the menacing ocean floor (which occasionally glances back). On a clear day, it might as well be Wind Waker.

But after dark, it becomes much more terrifying. The sun glides across the sky in almost every in-game action in Dredge, from navigating the ship’s wheel to rescuing a melancholic coelacanth from its ancestral refuge. Once it sets, a thick layer of fog covers the water, making it dangerous to navigate without a strong flashlight and bringing with it a host of new dangers. Not only does your ship lose hull points and, more painfully, cargo if it comes into contact with any solid object other than a dock jetty, but you also have to worry about your character’s sanity, which is symbolized by an eye that opens and closes. The more that eye twitches, the nastier and more otherworldly the water appears, with contours doubling and deteriorating into colors reminiscent of anaglyph-3D and rocks appearing inches from your bow.

These and the more active, roving hazards are initially unsettling, but as your ship grows tougher with upgrades and the resource-upgrade loop makes you less aware of the perils ahead, they lose their creep factor. Before long, you’ll be battling the twilight hours to pursue creatures that emerge just at night. However, the way that time is tied to motion still creates a subtle sense of anticipation, in part because it essentially paralyzes the cosmos when you pause to look about. Although enemies are readily avoided, even before you have a magical ability that temporarily repels them, you should not take them lightly. They all have their own unique sense of time, so there’s no stopping in the middle of a pursuit to laugh at a stop-clocked monster from the rear.

Dredge’s main flaw when compared to other exploration games with an RPG influence is how little it evolves. Subsequently, there are small amounts of automated manufacturing in the form of drift nets and crab pots. The former passively collects fish in your wake while the latter draws in crustaceans for you to gather a few days later (and makes for a very handy secondary inventory). Beyond that, the primary differentiator throughout the game is gaining velocity, which provides you the assurance to embark on longer expeditions without actually changing your tactics. The story doesn’t really progress either; if you know anything about Lovecraftian or Gothic sea stories, you’ll be able to spot its hidden mysteries from a mile away. There are several outcomes, all of which are dependent on a single, readily reloadable, late-game revelation and Big Decision.

It’s unfortunate that Dredge turns out to be so easygoing overall, since I believe that fusing horror with fishing points to a more expansive hypothetical connection between seas and computer code that might have served as the inspiration for something delightfully bizarre. Dredge’s main mechanism, reaching down from the graphical layer into an unfathomable extent of game data, portrays itself as cutting over the murky boundary between the seen and unseen components of the simulation. This is one of the game’s most alluring, yet ultimately unfulfilled, notions. According to the game’s own loading screen statement, “dredging the depths” is how the visible world is rendered. This conceit may have been an opportunity for horrifying surprises of a different kind in a project more focused on horror than playability or polish: fish that flatly refuse to be included in the progression systems, “sanity effects” that actively bend players’ perceptions rather than being a source of frustration, as if the calm archipelago of quest-loot-upgrade conventions were being undermined by the watery unknowns beneath the surface.

The way Dredge cheerfully squares off its own more bizarre flourishes, such as dropping a line into another dimension only to reel in creatures already blocked-out for storage and sale, may be even more horrifying than the plot itself, as it effectively conveys the idea of the ocean serving as a monstrous mirror for human appetites. The descriptions of the mutant fish in encyclopedias may make them seem horrible, but that’s merely stage dressing; they arrive already shaped into the same satisfying Tetronimoe forms as their “normal” brothers. The thing that makes them so ugly isn’t actually who they are, but rather their ravenous grid inventory.